Jet lag remedies don’t have to be complicated. With a few simple tweaks before, during and after your flight, you can reduce that groggy, out‑of‑sync feeling and enjoy more of your first few days away.

In this guide, we’ll walk through practical jet lag remedies that mature travellers can actually use: how to adjust your sleep, what to do on the plane, and smart habits for your first 48 hours in a new time zone.

What jet lag is (and why we feel it)

Jet lag happens when our body clock (also called our circadian rhythm) doesn’t match the local time where we’ve landed. Our bodies like patterns: light in the morning, darkness at night, meals at roughly the same times, and sleep that follows a steady routine. When we cross several time zones quickly, our body clock is still running on “home time” while the world around us has moved on.

That mismatch can show up as tiredness, trouble sleeping, headaches, brain fog, low mood, hunger at odd times, or an upset stomach. Jet lag isn’t a weakness or a lack of willpower. It’s a normal response to fast travel, and it usually improves as our body clock catches up.

In this guide to jet lag remedies, we’ll walk through simple steps you can take before, during and after your flight to reduce symptoms, sleep better and adjust to a new time zone faster.

What we can do before we fly

The easiest wins often happen before we even get to the airport. If we can spare a few days, we can start shifting our sleep schedule in small steps.

If we’re travelling east (where local time will be later than our body expects), we can try going to bed and waking up a bit earlier each day. If we’re travelling west, we can do the opposite and shift a bit later. Even 30–60 minutes per day can help.

We can also prepare by:

- booking the first day as a lighter day if possible

- packing sleep basics (eye mask, earplugs, pillow) where we can reach them

- planning how we’ll handle light and naps after landing (more on that below)

If you haven’t booked yet, it can help to compare different routes and layover options. We like using KAYAK and Trip.com to look at flight times, layovers, and arrival times side‑by‑side so we can pick the option that gives us the best chance of sleeping and arriving at a sensible time.

Choosing a daytime vs night‑time flight

When we have options, flight timing can change how jet lag feels.

A night‑time flight can work well if we can sleep on planes. It lines up with our normal sleep window and can help us land ready to stay awake through the new day. The risk is that if we don’t sleep, we arrive already running on empty.

A daytime flight can suit us better if we rarely sleep on planes. We can stay awake, then aim for sleep at a normal local bedtime after landing. The risk here is arriving at night feeling wired, then sleeping poorly.

There’s no perfect choice. The goal is to arrive with the best chance of following local time straight away. When we’re comparing fares and schedules, we look at:

- Departure time: Does it give us a relaxed start, or will we be exhausted before we even take off?

- Arrival time: Can we reasonably stay awake until local bedtime?

- Layovers: Long, awkward layovers can be just as tiring as a bad night’s sleep.

To play around with different options, we’ll often search flights on KAYAK, then double‑check options or deals on Trip.com before we book.

What we can do on the plane

Long‑haul flights can make sleep hard, but we can set ourselves up for better rest.

Sleep kit matters. An eye mask, neck pillow, and noise‑cancelling headphones (or earplugs) can reduce light and sound. Comfortable layers help because cabin temperatures change.

Set our clock to local time early. Once we board, we can switch our watch/phone to the destination time and start thinking in that schedule. It’s a simple mental cue that helps us decide when to try sleeping and when to stay awake.

Use naps with purpose. If it’s “night‑time” at our destination during the flight, we can try to sleep more. If it’s “daytime” at our destination, short naps (20–40 minutes) can take the edge off without wrecking sleep later.

On the plane we also try to:

- stand up and stretch every few hours

- keep caffeine to the local “morning” hours if possible

- drink water regularly, even if we don’t feel thirsty

- avoid working right up until trying to fall asleep

What we should do on arrival

After we land, our main job is to help our body clock match local time.

If we arrive during the day, we can try to stay awake until a reasonable bedtime. A short nap can be okay if we really need it, but keeping it short (about 20–30 minutes) is often better than a long sleep that steals the night.

If we arrive at night, we can aim to sleep close to local bedtime even if we don’t feel tired. A calm routine helps here (dim lights, warm shower, reading, slow breathing).

Natural light is a powerful reset tool. Getting outside can help our brain understand the new day. Morning light is often useful when we need to shift earlier, and late afternoon light can help when we need to shift later. We don’t need to overthink it: spending time outdoors in daylight is a good default.

Staying connected when we land also helps us quickly check local time, confirm hotel details, and avoid extra stress. We like using digital SIMs from Airalo so our phones work as soon as we step off the plane, which makes those first jet‑lag‑foggy hours a bit easier.

Sleep routines that help us adjust

Jet lag often improves faster when we keep sleep steady.

We can support sleep by:

- going to bed and waking up at the same time each day (as much as we can)

- keeping the room cool, dark, and quiet

- avoiding heavy meals right before bed

- using earplugs or white noise if we’re in a noisy area

- keeping screens and bright light low for the last hour before sleep

It also helps to accept that the first couple of nights may be uneven. Chasing perfect sleep can make us stressed, which then makes sleep harder. A consistent routine usually beats a perfect one‑off night.

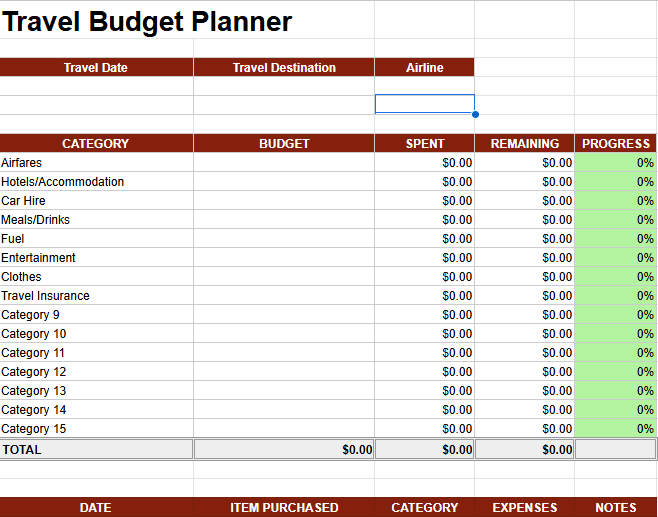

If we know we’re prone to worrying about sleep, it can help to plan a gentle first morning after arrival — perhaps a relaxed breakfast and light sightseeing rather than a packed tour. For more ideas on planning realistic first days and managing costs, you might like our guide to budgeting for trips, which uses the same steady, practical approach.

Hydration, caffeine, and alcohol

Cabin air is dry, and dehydration can make jet lag feel worse (headaches, fatigue, dry mouth). We can help by drinking water before, during, and after the flight.

Caffeine can be useful, but timing matters. If we use it late in the “new day”, it can push our sleep later and slow adjustment. A simple approach is to keep caffeine for the local morning and early afternoon, then stop.

Alcohol can make us sleepy at first, but it often leads to lighter sleep and more wake‑ups. It also adds to dehydration. If we drink, we can keep it small and early, then switch back to water.

We also like to travel with a refillable water bottle. If you’re moving through multiple countries or currencies, a low‑fee card like the Wise Travel Card can make it easier to grab drinks and snacks without worrying about ATM fees and poor exchange rates adding to the pain.

Meals and digestion across time zones

Our gut also follows a rhythm, so food timing can affect jet lag. When we eat meals at local times, we give our body another strong signal that we’re in a new schedule.

We can try to:

- eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner on local time as soon as we can

- choose lighter meals in the first day or two (especially at night)

- snack if we need to, but avoid huge late‑night meals

- focus on simple foods that sit well: fruit, yoghurt, nuts, soup, rice, lean proteins

If digestion is a problem, gentle movement, hydration, and regular meal timing often help more than skipping food for long periods.

Movement and exercise timing

Movement can help our energy and mood, and it can support sleep later on.

If we arrive during the day, a walk outside is one of the best all‑round jet lag remedies: it adds light exposure and gentle exercise at the same time.

If we arrive at night, we can avoid hard workouts close to bedtime because they can keep us alert. Stretching, an easy walk, or light mobility work can help us wind down instead.

If you plan to hire a car after a long‑haul flight, it’s worth being honest about how alert you’ll feel. Sometimes it’s better to book a first night near the airport, then pick up a rental later. When we do rent, we like booking through DiscoverCars so we can compare options and choose something comfortable and easy to drive on tired eyes.

Melatonin: when we might consider it

Melatonin is a hormone our body makes to support sleep timing. Some people use melatonin supplements to help shift their sleep schedule after crossing time zones.

If we consider melatonin, timing is key. It’s usually taken 30–60 minutes before the bedtime we want in the new time zone. Taking it at the wrong time can make things worse.

Because melatonin can interact with some medicines and isn’t right for everyone, it’s sensible for us to check with a GP or pharmacist first, especially if we’re pregnant, have health conditions, or take regular prescription medicines.

We also like to think about travel insurance before long trips, especially if we’re managing health conditions or new medications. You can compare flexible policies with providers like VisitorsCoverage, which offer options tailored for international travellers.

Planning our first 48 hours

The first two days are where we can make jet lag smaller, or larger.

A practical plan looks like this:

- land, hydrate, and eat something light on local time

- get outside for daylight (even 20–30 minutes helps)

- keep naps short and early if we need them

- schedule important tasks for when we’re most likely to be alert

- protect the first local bedtime with a calm routine and low light

Most of all, we can give ourselves permission to take it slower. Jet lag is temporary, and pushing too hard often backfires.

If we keep these steps simple — shift sleep a little before we go, stay hydrated, use daylight, keep naps short, and follow local time — we can reduce jet lag and enjoy more of the trip from day one.

Jet Lag Remedies FAQs

How long does jet lag last?

How long jet lag lasts depends on how many time zones we cross, our age, and our general health. A common rule of thumb is about one day of adjustment per time zone crossed, but many people feel noticeably better within 3–5 days.

Travelling east (for example from the US to Europe) often feels harder than travelling west, because it means going to bed earlier than our body wants to. Good jet lag remedies — like using daylight, keeping naps short, and eating on local time — can shorten how long it bothers us.

Should we force ourselves to stay awake if we’re exhausted on day one?

We don’t need to force ourselves to stay awake at all costs, but it does help to protect the first local bedtime. If we’re exhausted on day one, a short nap (20–30 minutes) earlier in the day can take the edge off without ruining night‑time sleep.

What we try to avoid is a long, late afternoon nap that leaves us wide awake at 2am. If we absolutely have to nap later, we keep it short, set an alarm, and still go to bed at a normal local time.

Is it better to sleep on the plane or stay awake?

It’s usually better to match the destination time rather than follow a strict “always sleep” or “always stay awake” rule.

- If it’s night‑time at our destination while we’re flying, we try to sleep more, even if it’s broken sleep.

- If it’s daytime at our destination, we keep sleep to short naps so we can still fall asleep at a normal local bedtime after landing.

Some people simply can’t sleep on planes, and that’s okay. In that case, we focus on resting with our eyes closed, staying hydrated, and planning a sensible first day with lighter activities.

Watch Our Video On Jet Lag Remedies